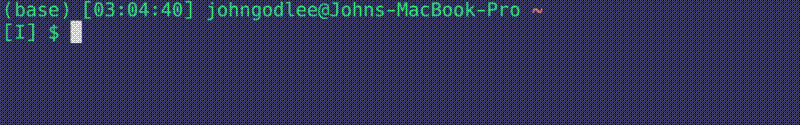

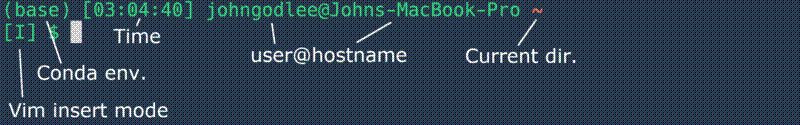

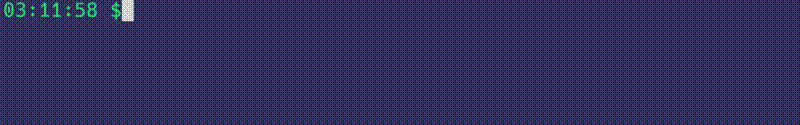

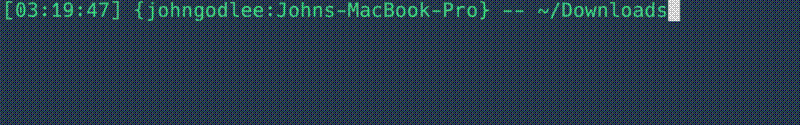

This is what my bash prompt looks like at the moment:

Here is what the various parts refer to:

And here is a link to a .bashrc,

What is a bash prompt?

The bash prompt is a piece of text placed at start of a command line interface using the bash shell. The primary function of the prompt is to let the user know that the computer is ready for the next command, the secondary function is to provide the user with some information about the status of the current session.

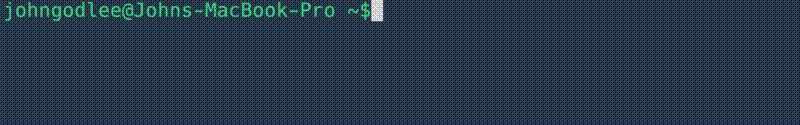

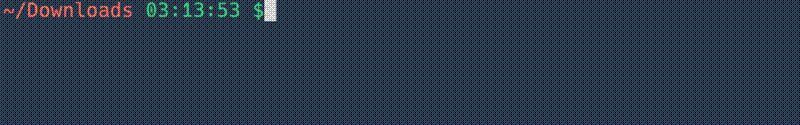

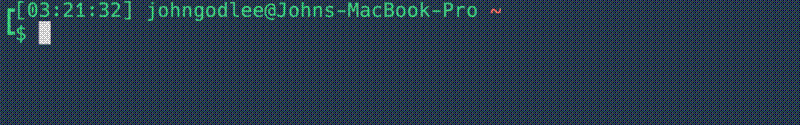

The default bash prompt looks like this:

so fire up your terminal of choice and see that your bash prompt looks similar. The default prompt shows the currently logged in username, the hostname (i.e. the name of th computer), the current directory path relative to ~ and finally a $, which marks the end of the prompt and the start of the area that you can type commands.

Customising the bash prompt

The .bashrc, among other things related to how bash functions, is where you can define a custom bash prompt. .bashrc is normally found in the root (~) directory. Check if you have a ~/.bashrc using:

cat ~/.bashrc

If bash says that there is no such file, create one using:

touch ~/.bashrc

Finally, start editing .bashrc using your favourite text editor, e.g. vim:

vim ~/.bashrc

Super basic

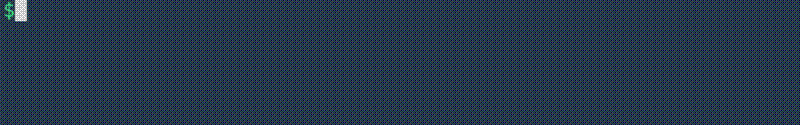

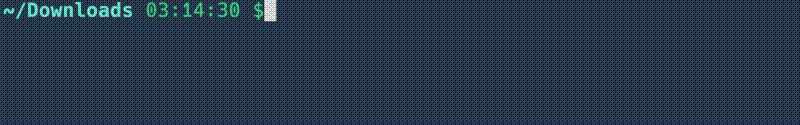

To start with, let’s replace the default bash prompt with something really simple like this:

To achieve this, type the following into your .bashrc:

PS1='\$'

Then exit the text editor and enter the following into the terminal, which forces bash to reload .bashrc:

source ~/.bashrc

PS1 refers to only one of five bash prompts, with PS1 being the default prompt that is shown most of the time; PS2,PS3,PS4 and PROMPT_COMMAND are used under special conditions. This article

has a good description of what they’re used for.

Incorporating variables

The simplest way to add a variable (i.e. something which changes depending on environment conditions, like the current working directory) is to use one that bash understands by default, a full list of which can be found here .

Start by adding the time to our simple $ prompt:

PS1='\T \$'

Note the space between \T and \$. Adding spaces between variables can help everything to look neater.

Read through the list of available variables and add a few to your own prompt.

Colours

To change the colours parts of the bash prompt, wrap the variable in ANSI escape sequences, like so:

PS1='\[\e[31m\]\w\[\e[m\] \T \$'

This makes the directory path appear in red text. 31m is the section of that sequence that actually defines the colour red.

ANSI escape sequences can also be used to change the background colour of the text, add underlines, make the text bold, or high contrast. I often refer to both this wikipedia page on ANSI colour codes and this blog post on jafrog.com when choosing colour codes.

A more elaborate example which makes the current directory light-cyan coloured, with bold font:

PS1='\[\e[96;1m\]\w\[\e[m\] \T \$'

The ;1 is the part which makes the text bold. Note how [\e[m\] always needs to be placed at the end of the coloured part of the bash prompt, to return the colours to normal.

Try colouring the time (\T) so it is underlined and magenta.

Unicode characters

Another way escape sequences can be used is to add unicode characters to the prompt, whether this is a cool lightning bolt, a tick or a cross, or any of the other 136,000 characters available in Unicode 10.0.

Wikipedia has an excellent resource for browsing unicode characters

Browse through the wikipedia page and pick your chosen character, then note down its code, e.g. u2602 for the umbrella symol. The syntax for adding this to your bash prompt is as follows:

PS1=$'\u2602'

Note that inserting unicode can also by accomplished just by copying and pasting the unicode character itself into the .bashrc.

Note how the $ isn’t escaped this time, as we don’t actually want to see the $ in our prompt

Formatting

Brackets, spaces, hyphens, colons can all be used to great effect in your bash prompt to help separate the different parts. As an example, try setting this in your .bashrc and source ~/.bashrc to see the results:

PS1='[\T] {\u:\h} -- \w'

Building PS1 incrementally

After a while, if your bash prompt becomes long and complicated, your PS1 code may start to look busy and hard to read, but it’s easy to restructure the PS1 code to increase readability. In the example below, a long and complicated prompt is rewritten so each part is on a separate line and spaces are given their own lines to make them easier to see. Additionally, this allows each part to have its own comment, further increasing readability:

# Messy one liner

PS1='┏[\T] \u@\h \[\e[31m\]\w\[\e[m\]\n┗$ '

# Tidy on multiple lines

PS1=$'\u250F' # Elbow

PS1+='[\T]' # Time

PS1+=' ' # Space

PS1+='\u@\h' # User@hostname

PS1+=' ' # Space

PS1+='\[\e[31m\]\w\[\e[m\]' # current dir

PS1+='\n' # New line

PS1+=$'\u2517' # Elbow

PS1+='\$' # $

PS1+=' ' # Space

Conditional statements and functions

From here onwards I am writing about stuff I don’t fully understand and have just gathered from other websites and tutorials.

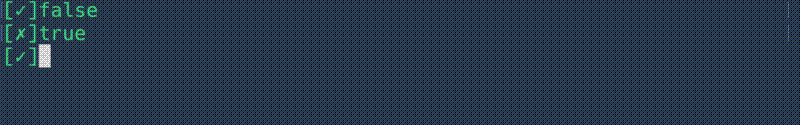

If you want to expand the number of variables you can use in your bash prompt you can take create functions in your .bashrc, which you then source in your PS1 code. The example below (which I adapted from here

) shows how to present a unicode tick if the previous command was successful, and a unicode cross if it was unsuccessful, add the following to your .bashrc:

SUCCESS='[✓]'

FAIL='[✗]'

error_test () {

if [ $? == 0 ]; then

echo -e $SUCCESS

else

echo -e $FAIL

fi

}

## Bash prompt

PS1="\$(error_test)"

Note the __stat. As far as I know the __ aren’t necessary, the function could just be called stat, but it seems to be a common convention in bash prompt functions.

Sourcing external scripts

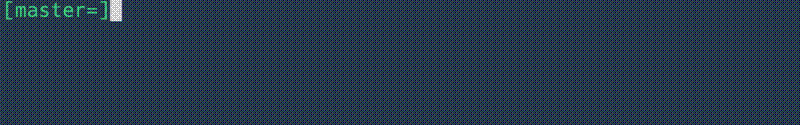

I use the git-prompt.sh shell script

, which is part of the contributed materials in the git github repo, to get the current git branch displayed in my bash prompt. Download and save the script in the link as ~/.git-prompt.sh. Then add the following to your .bashrc:

source ~/.git-prompt.sh

PS1='$(__git_ps1 "[%s]")'

git-prompt.sh also has some variables which can be set from within .bashrc. Details can be found by reading the preamble of the script in a text editor.

Now that you’ve read through the tutorial, try to construct your own bash prompt, adding the bits that you find useful. Refer back to the linked .bashrc for some inspiration.