Over the Summer I spent just under a month in the Republic of Congo, doing some fieldwork for a colleague.

The work was to carry out yearly measurements on open-woodland savanna plots, then to burn the plots afterwards.

The field sites were located in the Bateke Plateau, which is really interesting biogeographically speaking. The region covers around 6 million hectares, stretching across the Congo into The Gabon to the North and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the South, and is the remains of a vast sand dune system formed during the Eocene period, ~50 million years ago. The deep, rolling dunes have been colonised by grass and relatively scattered trees, except along river valleys where there are ribbons of dense gallery forest.

I flew into Brazzaville, the capital city of the Congo and met with people from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), who had connections to the US Forest Service and were responsible for organising my transport, housing, students etc. We spent a few days getting everything ready, then took a truck up to our first field site. My field team consisted of three Master students from the Marien Ngouabi University in Brazzaville and a group of around 10 day labourers that we employed from villages near our field sites. We worked at two field sites, each with three 25 hectare plots of savanna. Each of the plots per site had a different experimental treatment. The first was to be burned at the start of the dry season, the second at the end of the dry season and the third was to be kept as a control and never burned. The idea of the experiment is to see whether regular burning at different times of the season effects the intensity of the fires and therefore the species that grow there. If the fire is later, there should be more biomass and therefore a hotter fire, which would cause more tree mortality and potentially change the species composition of the grasses. As the climate changes, it is likely that changes in temperature and precipitation regime will cause the fire season to change, and some of the changes we’re seeing experimentally in the vegetation could start to be seen across the whole landscape.

In each plot we had a number of jobs to do. Firstly, we had to go round each of the ~1000 trees in a plot and measure its trunk diameter (Diameter at Breast Height (DBH)) and make notes of whether any of the trees were dying, had fallen over etc. Then in each of the subplots we took measurements of the grass height using a wooden disc that we rested on the top of the grass.

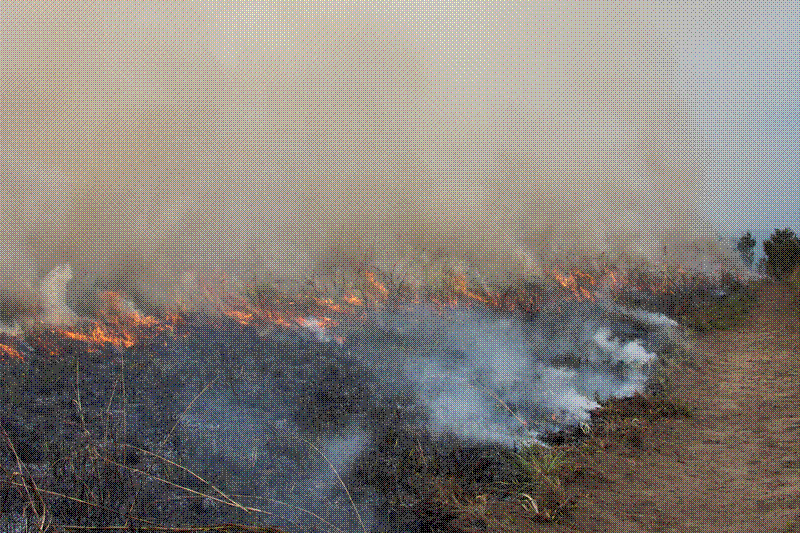

After we had conducted all our measurements and the fire breaks had been dug properly by the day labourers, which took about 8 days per site, we set fire to the plot! The fire lighting technique used by the local people is to bundle grass together, light one end and drag it along the edge of the plot to be burned, so bits of smoldering grass break off and start small fires all along the perimeter of the plot. Afterwards we estimated how patchy the fire was by measuring how much of the subplots had burned and estimated fire intensity by measuring the height of the highest singe mark on the bamboo poles we planted. It was surprising how quickly the plot burned, only about 40 minutes for 25 hectares, and how quickly the ground cooled down afterwards, we could take our measurements about 10 minutes after the fire had finished burning.

Aside from the obvious logistic complexities in completing the experiment and shipping all our gear to a remote field site we also had to navigate various security checkpoints set up by the military and the police, who serve the current government. Since the last election in 2015 there has been an increasing frequency of short periods of civil unrest in the region directly around Brazzaville, mostly in the area directly outside of Brazzaville. From what I heard, most of the sporadic fighting in rural areas has been organised by Pastor Ntoumi, who controls a militia that has been operating since the civil war in the 1990s, though it was ‘officially’ disbanded in 2009. This is also despite many reputable sources saying thayt Ntoumi took up a government post in 2009, presumably ending his involvement in anti-government militias. At one point we had our passports taken and were taken from our truck, and a few times we had to pay small bribes. It didn’t get dangerous, but in retrospect it could have been.