I’m now just over 1 month into my 48 month PhD program. I’ve spent a lot of time reading and trying to wrap my head around my project. Now I feel like I’m ready to at least have a stab at saying what my PhD is going to be about. Though this all might change again over the next few months as I start to write my PhD plan and confirmation report.

The original title of the PhD I applied for was “Biodiversity – Ecosystem Function Relationships in Southern African Woodlands”. The basic idea that has been reported by lots of independent studies is that as biodiversity increases, so do the levels of various ecosystem functions. Biodiversity is most commonly measured as species richness (i.e. the number of species in a given area). Ecosystem functions are just any rate process that the ecosystem performs, one of the most commonly used is the rate at which CO2 is fixed into biomass via photosynthesis, taking into account respired CO2. This idea has been used a lot to justify biodiversity conservation work, under the assumption that if biodiversity declines, ecosystem functions and their associated benefits to humankind will also decline.

There is however, still lots of controversy about how strong the effects of the BEFR are in natural systems and what the drivers of the BEFR are. A lot of studies of the BEFR have been in mesocosms, or small grassland patches. These studies are often criticised for not mirroring natural systems enough to be used to inform policy. Often they study one ecosystem function within a limited timeframe and with a small species richness. Often species addition/removal is random, which doesn’t mirror what happens in natural systems under stress.

In the past, studies have identified the following as potential drivers of the BEFR:

- Niche complementarity - As more species are added, they necessarily differ in the niche space they occupy so they can fill more of the total niche space and optimise resource usage.

- Selection effects - As more species are added, there is a higher probability that one of those species will maximise productivity. e.g. Grimes 1998

The above potential drivers of the BEFR differ in their reasoning. Niche complementarity doesn’t take into account community composition, while Selection effects realy on community composition. Of course, it’s likely that in a natural system it’s probably a combination of the two.

Of course there are other reasons why ecosystem functioning, e.g. productivity might vary over space:

- Resource availability - As resource availability increases, productivity responds to that by increasing productivity

- Environmental stress - An increase in environmental stress such as fire intensity might lead to an increase or a decrease in productivity, the exact mechanisms behind this are complex.

Southern African Woodlands are understudied and unique

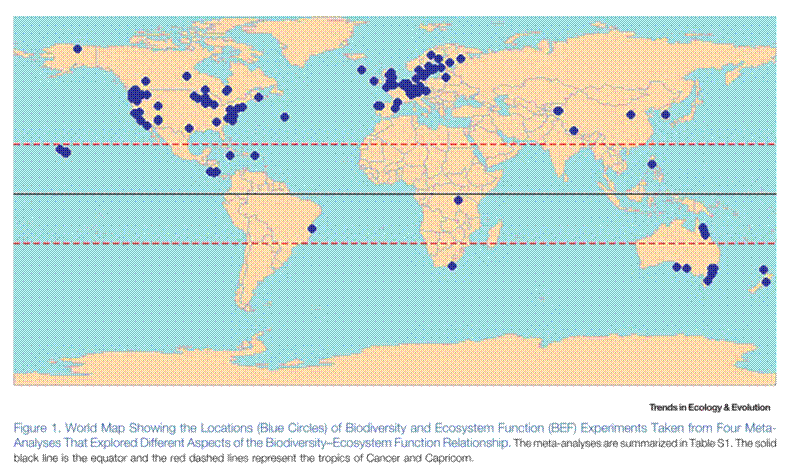

The “Southern African Woodlands” bit is part of why this project is interesting. The map below from (Clarke et al. 2017) shows that African study sites (and the tropics in general) are severely under represented in the Biodiversity - Ecosystem Function (BEFR) literature.

Also, a lot of these theories about the BEFR were drawn from studies in temperate environments, so it’s not a given that the same processes will occur in the dry tropics. Indeed, in the wet tropics, there isn’t such a strong BEFR, and there are various reasons for that. One of the trains of thought that is getting a lot of attention at the moment is the role of the environment in mediating the strength (i.e. the steepness of the slope), of the BEFR. In the temperate studies, it’s often found that as you decrease resource availability, facilitation effects become stronger than competition effects, so that if you add another species to the ecosystem, the ecosystem functioning is likely to go up more than if the community was under no stress and species were competing more. I’m not sure I agree with that idea, surely in a woodland, even if there is drought stress, the trees are still going to compete for that little water availability because they are close together. The competition effect might even increase.

There isn’t much data on the traits of different species in African woodlands, but it makes sense that species with different traits would react differently to environmental change, so the structure of the woodland is going to change as different populations change in abundance depending on their response to environmental change. It also makes sense that as the relative abundance of each species changes under environmental change, the level of various ecosystem functions will also change at the plot level, because different species provide different ecosystem functions. These two sources of variation between woodlands muddy the waters in the search for a general BEFR, but possibly if you can control for those sources of variation, or at least account for them properly in statistical analysis you could go some way to teasing out a relationship.

Possible studies

Obviously one of the main jobs of this PhD is to use data from many woodland plots across Southern Africa to try to quantify the BEFR, and figure out what the drivers of the BEFR are. For example, does the shape of the BEFR vary across space according to water availability. How does it vary according to woodland type.

I’d like to do a study that looks at how different woodland types and their species composition (i.e. their biodiversity) affect how they will respond to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations. For example, some woodlands might be made up predominantly by a single species that is very fast growing and can take advantage of the extra CO2, while others might not. I suppose leaf traits would also have a lot ot do with this. I’ve heard of a general distinction between species that invest in woody growth, and those that invest in leafy growth, maybe that has something to do with it.

I think that the understorey of savanna-woodland mosaics is understudied. You might expect that the structural aspects and diversity of a woodland canopy might affect the diversity and composition of the understorey. Understorey species might affect the provision of rare ecosystem services and functions, they will also have a big role in the spread of fire through those understories.

Lastly, it looks like I might be going to Angola for 2 weeks in January, to get involved in overseeing the collection of some data that will get put into the SEOSAW database. The trip should be a good chance for me to get some more fieldwork experience (go to a cool place) and make some connections with the people who are collecting the data. Making these measurements will be one of the first cataloging efforts in the woodlands in this part of the African continent and could be a neat paper in itself if I can make some connection between the initial biomass and its partitioning amongst species of different traits. That study would also be a nice way to kick off a second PhD chapter on the role of community composition on the BEFR. Then I’d have a chapter on the role of environmental variation on the BEFR.

The lack of a BEFR in the wet tropics, possibly worldwide

In the wet tropics, species richness is very high to begin with. Many studies of the BEFR in experimental landscapes have shown that the BEFR saturates at high biodiversity, so maybe if you take away a species it won’t actually make any difference. This equates to there being high functional redundancy in the wet tropics. The most plausible theory in my mind as to why this is the case is that because environmental conditions are quite amenable, it is likely that competition interactions are powerful enough that species co-exist, even within the same niche space, at least at the plot scale and higher, this leads to a lot of functional redundancy. If you remove a species from the niche space, a suitably similar species will have the ability to fill that niche space quickly, so there is no loss of function.

In dry ecosystems however, there aren’t that many tree species to begin with, so you would expect there to be a big effect on productivity if you removed a species, as a big area of niche space has been removed. However, this line of reasoning relies on the assumption that the tree species occupy different niches, while occupying adjacent space, but adult trees in savannahs might not compete with each other due to them being so spaced apart. So, instead of there being a species richness - function relationship, maybe there is a composition - function relationship, and the function merely relies on the presence of certain species over others.

Early predictions

y thoughts at the moment are that because African woodlands are quite species poor to begin with, the addition of a tree species could greatly increase the productivity of the woodland. But I also expect that this effect will depend on a minimum threshold of tree density to begin with. At really low tree densities the effect of adding a species would depend more on the productivity of that species, because the niche space isn’t filled enough to promote niche partitioning.