This post is going to sound very preachy, but I do think it’s an important topic, and something that’s easily overlooked during ecological fieldwork.

When I’m working with a team of people to construct a vegetation survey plot, one person is normally tasked with writing down measurements in a notebook or on a data sheet attached to a clipboard, a scribe. That person needs to write down the measurements quickly, in an organised fashion and neatly, so that the measurements can be later transferred to a computer. It’s not an easy job, and it carries a lot of responsibility.

Reading through old notebooks, there are a number of times when a hastily written number or letter has left me wondering about the correct value. Over time I’ve tried to adapt my handwriting to minimise ambiguity of each character.

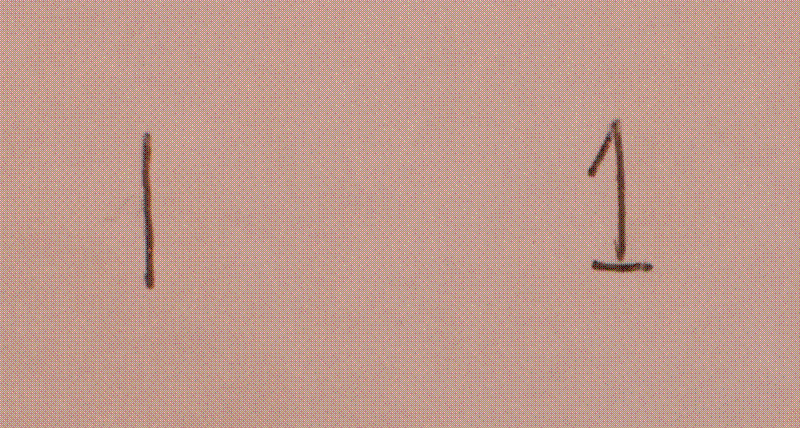

For example, it’s tempting to write the number 1 as a straight line, but this can easily be misinterpreted as a straight line, i.e. part of the table architecture, or the letter ’l’. It’s also easy for an un-serifed straight line to blend into the border of a table, or into the page margin. I always aim to put a hat and a base on the number 1 to make sure it can only be that character.

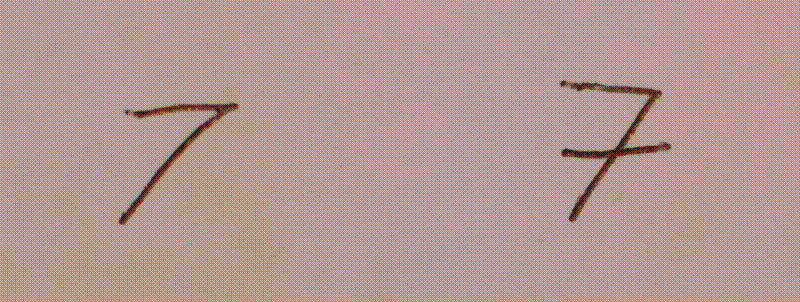

Even with the embellishments on the number 1, a major problem can still occur from misinterpreting a 7 as a 1. I put a horizontal line through the body of the 7, to make sure it can’t be mistaken for a 1.

One problem I haven’t managed to solve is how to make sure a 5 can’t be mistaken for an ’s’. In most cases it doesn’t matter because numbers and letters are rarely combined in the same cell, but at least once I’ve had to fill a table cell with stem mortality notes, one of which is whether the stem is standing (S) and one of which is the condition of the stem (1-5 scale). It’s important to ensure the top of the 5 is angular, but I wonder if there’s a completely different glyph to describe the number 5 which I haven’t thought of.

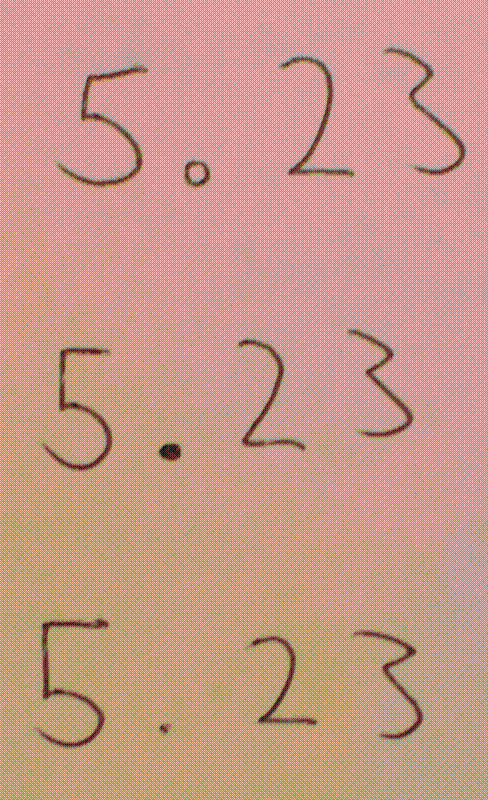

When recording stem diameter measurements it’s extremely important that the decimal point is in the right place. As an example, using the equation from Chave et al. (2014) and the Worldwide wood density database from Zanne et al. (2009), a Brachystegia spiciformis tree in Bicuar National Park, Angola, with a diameter of 5.3 cm has a biomass of 0.0049 t DM^-1 (dry matter), while the same tree with a diameter of 53.0 cm has a biomass of 1.6821 t DM^-1. While the difference in DBH is only a factor of 10, the biomass is increased 343 times. Writing decimals as a dot isn’t sufficient, especially when using a pencil. Instead I always try to write the point as a filled circle, which admittedly take a bit more time. Aligning the decimals in a table column can also help to catch any obvious errors in decimal placement, and means you can fill in the decimal points later during a free minute.

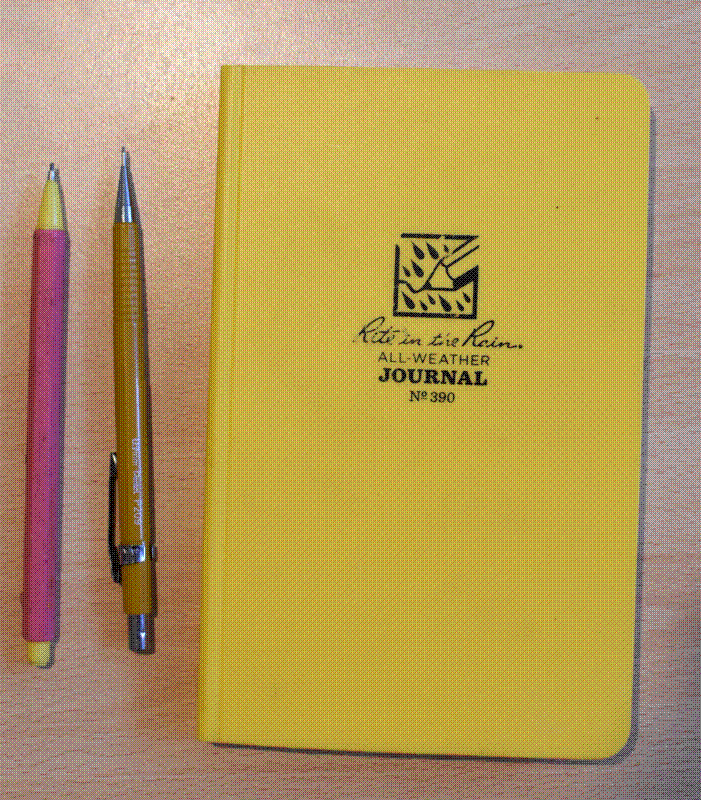

Writing implements are an important consideration. I use a Rite-in-the-rain No. 390, a waterproof hardback notebook with ruled pages. I always use mechanical pencils to make sure my measurement recording is precise. Normal pencils become blunt very quickly and it’s a pain sharpening them in the field. My favourite pencils are the Kokuyo Campus Junior 1.3 mm Pink (PS-C101P-1P), and the Pentel 0.9 mm Yellow (P209). Notice that both pencils are gaudy colours so if they drop on the ground I don’t lose them in the undergrowth. I change my mind regularly on the best diameter pencil lead. I think it’s really just personal preference.

Part of the responsibility for writing precise and clear measurements lies with the person reading out the measurement. Consider an example where researchers are weighing the fresh weight of dead-wood samples on the forest floor using a set of digital hanging hook scales. The measurement is 1432.54 g. Instead of saying “one thousand four hundred and thirty two point fifty four”, say “one four three two point five four”, it removes a lot of ambiguity. Similarly, if a tag number on a tree is 344A, don’t say “three hundred and forty four A”, or even “three double four A”, say “three four four A”. When a lot of measurements are being read out one after another, try to say them in the same order each time, and call out the name of the measurement first, so the scribe’s hand is primed at the correct place on the page, for example: “DBH fifty one point two. Height twelve point five one, condition standing and topkilled”.