This post describes the process I went through with the Woodland Trust MOREWoods tree planting scheme, to plant 10 acres (4.05 hectares) on some farmland in North Yorkshire.

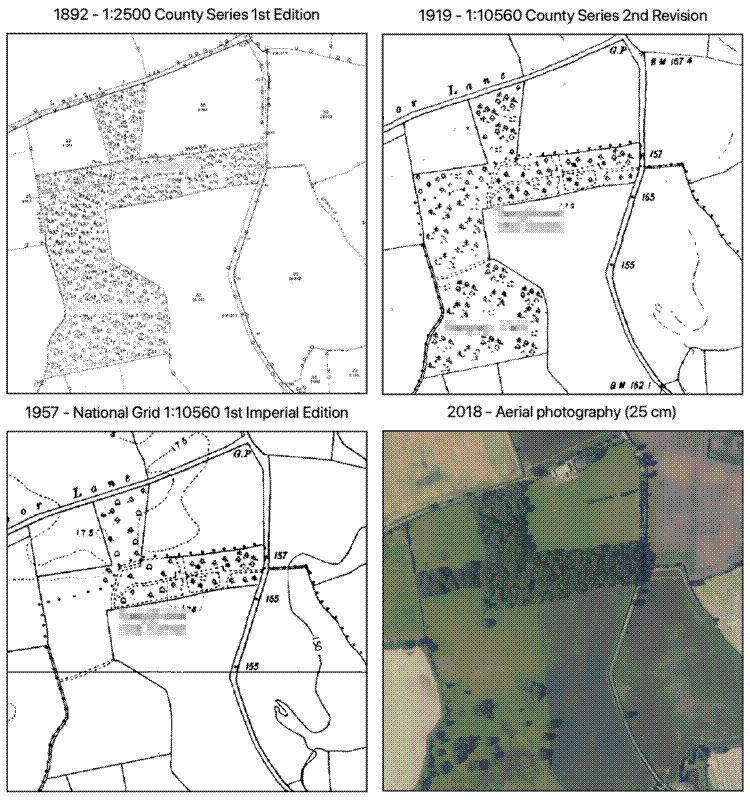

I found historical maps through the University of Edinburgh Digimap service which showed that some of the pasture on our farm had previously been woodland. The images below show what the woodland looked like in 1892, 1919, 1957, and 2018. Clearly at some point between 1919 and 1957 a large portion of the woodland was felled. This is the area I aimed to re-plant. Since at least 1957, the land has only been used as rough pasture for sheep and cattle.

In addition to previously being woodland, the other main reason I wanted to plant this area was to increase the size of the existing woodland. Some plant and bird species require the darkness and humidity of a deep woodland interior to thrive, which they weren’t getting in the current woodland. Finally, I wanted to make better use of the land than rough pasture. The soil is relatively thin, with a well-drained gravel pan only about 30-50 cm below the surface. The grass has never been particularly productive and contains a lot of moss, probably a result of over-grazing.

Although I started to think seriously about woodland planting in summer 2018, we didn’t officially lodge our application with the MOREWoods scheme until May 2019. We looked around a few schemes which provide subsidies for tree planting. Some of the larger grants weren’t suitable for us because of complications caused by renting the land out to a tenant farmer at the time of application. MOREWoods was a good option for me because I am a novice at land management and the grant provides guidance from a qualified consultant who can help with planning what species to plant, where to plant them, and how to manage the trees after planting. The initial application was fairly easy. We had to provide a map of the area to be planted, and confirm things about land tenure and current land usage. MOREWoods agreed to pay for 80% of the cost of trees and guards because we are within the Woodland Trust’s Northern Forest region.

After we passed the initial Woodland Trust (WT) screening process we started to look at how we would take the land back from the farm tenancy. For many years the pasture and arable fields on the farm have been rented out to tenant farmers. Farm tenancies have much longer notice periods than houses, we had to give a notice period of almost a full year to take back the land, and the handover had to happen on the 1st January, to fit with the farming calendar and the subsidy payment schedule. Also, according to the tenancy, we were only allowed to reclaim up to 10 acres per year, unless we gave notice for the entire farm, which entails its own difficulties.

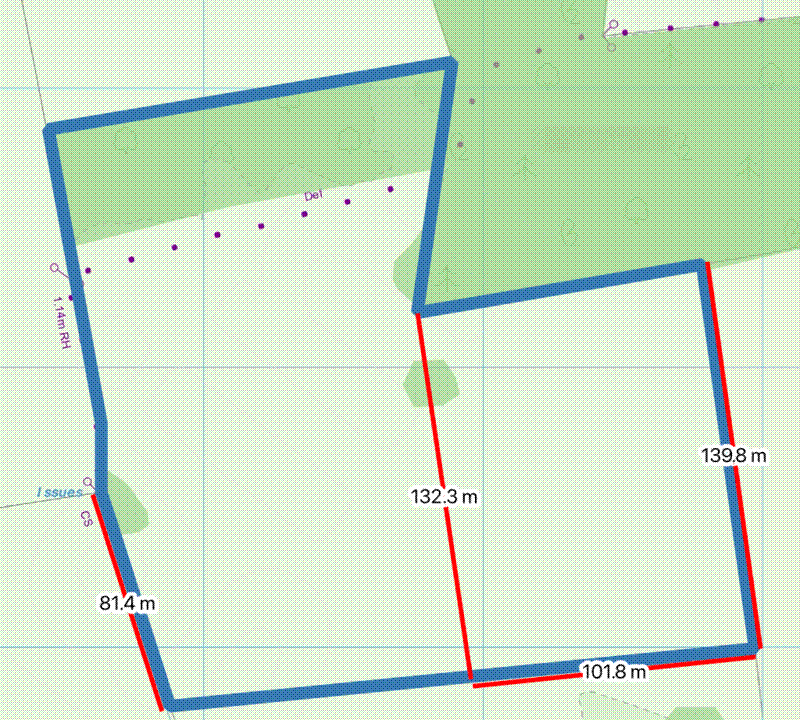

The farm tenants were quite worried about correctly marking the fencing line which would divide the field so we could plant one part of it. Apparently the farming subsidies can be quite strict about misrepresenting field sizes, and often impose penalties if a field has been measured incorrectly. To mark the field I used QGIS to draw an area of exactly 10 acres, using an OS 1:2500 map as a guide for the field boundaries. I tried initially to use satellite imagery, but because of the overhang of hedges and trees I found it difficult to accurately determine the boundaries of the field. I measured the distance from known points along the existing fence lines to determine the new fence line. On-site we used a trundle wheel to measure those distances and marked the new fence line at both ends with iron rods driven deep into the ground. In hind-sight, we should have used a tape measure rather than a trundle wheel, because the uneven ground messed up the distance measures a bit, but eventually we came to a fence line that everybody agreed on.

Unfortunately even though the Woodland Trust approved our application in August 2019, it took until April 2020 to organise a consultant to survey the land and discuss species mixes. Then after we sent off the report based on the consultation, it took the WT until August 2020 to realise that they actually needed an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) from the Forestry Commission, because the new woodland is >3 ha. The process for the EIA was slow. We had to consult “local stakeholders” via the Parish Council, adjacent land-owners, and also the local authority archaeology department. The archaeology people had an issue with a small part of the planting site which appeared from a satellite image to have an old ridge-and-furrow (rigg and furr) system. We were skeptical of this assessment, especially as they hadn’t conducted an on-site survey, but to avoid further delay we complied with their wishes and left part of the planting area as open ground. After gathering all these consultations the EIA took until December 2020 to be approved, then until mid-January 2021 to actually sign the contract from the WT. I think the WT offices had difficulty processing applications because of COVID restrictions which meant their staff were sometimes working from home. On the whole however, I was disappointed with the service from the WT. It seemed like a lot of stress could have been avoided if the WT had pushed the process along a bit quicker, rather than waiting for months between each stage. I was also disturbed that although our application was described “approved” in 2019, it clearly wasn’t and there were many more hoops we had to jump through before there was truly no going back. It would have been very annoying if we had taken back the land from the farm tenancy only to later find out that the MOREWoods grant wouldn’t pay out.

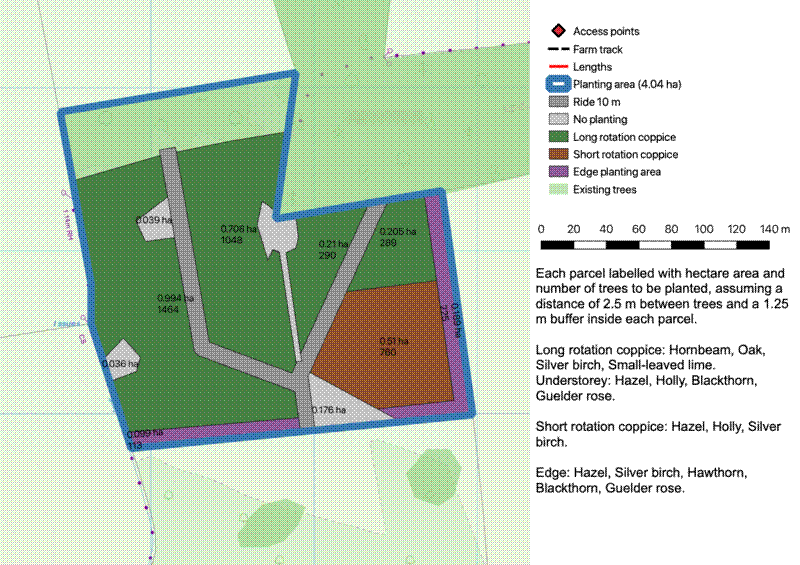

I was given a lot of control over the species mix of the new woodland. I opted for two main zones (compartments). The larger compartment is dominated by pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) and Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), both large canopy trees with long lifespans and which provide decent hardwood for building and firewood. The smaller compartment is dominated by silver birch (Betula pendula) and hazel (Coryllus avellana), shorter lived species which coppice well and can provide us with smaller poles and canes, which are useful for making hurdles, or for smaller firewood. We weren’t allowed to plant ash (Fraxinus excelsior) because of the likelihood of it succumbing to ash dieback, though there is a lot in the existing adjacent woodland. In addition to the principal species, we also included shrubs and other species at lower percentages scattered throughout the compartments, simply to increase biodiversity and to have a bit of variety.

Below is the full breakdown of species and which compartment they go in:

| Compartment | Alder | Blackthorn | Birch | Alder buckthorn | Hazel | Hawthorn | Hornbeam | Holly | Wild cherry | Oak | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Rotation Coppice | 0 | 0 | 300 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 50 | 825 |

| Long Rotation Coppice | 0 | 150 | 500 | 75 | 350 | 0 | 950 | 75 | 350 | 900 | 3350 |

| Edge Shelter Belt | 0 | 100 | 150 | 25 | 100 | 75 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 500 |

| Alder Carr | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| ———————- | —– | ———- | —– | ————— | —– | ——– | ——– | —– | ———– | — | —– |

| TOTAL | 50 | 250 | 950 | 100 | 850 | 75 | 950 | 200 | 350 | 950 | 4725 |

To generate these numbers I started off by calculating how many trees would fit in each compartment based on the compartment area and the 2.5 m distance between each tree. Then for each species in each compartment, I decided what percentage of the trees I would like from each species in each compartment. Then I divided the total number of trees by the percentage to get the number of trees per species. Because the trees come in bundles of 25, I then had to round up or down to the nearest 25.

The alder area is located in a patch which gets flooded seasonally. Alder (Alnus glutinosa) can deal very well with wet conditions, so I thought it would be the best species for that area. We left a bit of a marshy pond bit in the middle which can act as a habitat as the woodland grows. We left a couple of open glades in the woodland in the hope that these will also increase biodiversity by providing open but sheltered areas, popular with butterflies and bees.

The edge belt is there primarily to provide some shelter at the edge of the woodland, so that the wind doesn’t blast through the understorey. Planting a shelter belt can drastically alter the micro-climate in the understorey, hopefully providing a warmer and wetter environment that is more suitable for insects, small mammals, and wildflowers. It also means there is more of a natural barrier should any livestock eventually break through a fence.

Finally there is a wedge-shaped patch at the southern end of the site near the gate which we have left empty so that we can use it for other things. Helpfully this patch coincides with most of the area the archaeology people wanted to leave un-planted. I’m hoping to install some bays that we can use to process and keep wood in before it is transported nearer the house for drying. Also I’d like to have a bay for wood-chippings, which we are going to use as mulch around the base of the trees to keep weeds down.

By the time we got to mid-December 2020 it was clear that having volunteer groups in to plant the trees, as had been the original plan, was untenable because of COVID restrictions that meant we couldn’t safely house or feed the volunteers if they needed to stay overnight. Instead we opted to use a professional tree-planting company who are based nearby and who came recommended by a family friend. The tree-planting company cost a lot of money, but under the circumstances it was the only safe option. I still feel guilty for not involving the community more, but circumstance forced my hand.

Our trees were delivered on pallets by a lorry with a forklift on the back. We loaded as much as possible onto a trailer, and transported it in batches over to the planting site. Most of the volume of the delivery consisted of tree guards and stakes. The 4725 trees all fitted onto one large pallet. The trees arrived bare rooted in plastic bags, which meant they had to be planted ideally within about 7-10 days.

The tree-planting company marked out the different compartments of the planting site with bamboo canes with flagging tape attached. I helped with this process because there were a few adjustments and judgement calls to be made since the gate holes and therefore the 10 m wide track had changed position from when I made the planting map. The tree planting company used an Android mapping app with an overlay of the planting area I had sent them to mark out the different areas. I thought this worked well, but I felt that they relied on it a bit too much and I had to pull them back a couple of times on common sense issues. See the image below where some trees have been planted under an overhanging hedge tree, which is probably not the best idea.

I helped with some of the planting, and learned a lot about how to find the rhythm when planting many hundreds of trees, but mostly I left the professionals to it and just checked in every day to see if they had questions or problems. They planted in rows to allow easy access for mowers, but offset each row so that from most angles the trees appear more naturally distributed. I thought this was very effective at breaking the visual lines. See the photo below. Mostly the tree planters didn’t use any special equipment, only tree-planting spades, hammers, and bamboo canes, but one incredibly useful addition to their arsenal was a John Deere Gator Utility Vehicle , which looks a bit like an off-road golf cart. It allowed them to quickly move stuff around the site without churning up the wet ground. If they had relied on wheelbarrows instead it would have taken much longer to get set up.

After the tree planters had left, we did a few checks to make sure everything was in order. We walked through each tree and looked for:

- Trees without guards

- Guards with too few zip-ties

- Trees with bent over main stems

- Trees where the main stem or a substantial branch was threaded through the zip-tie

Fixing all these small issues, while tedious, is definitely worth it, as without correction they will severely impact the growth of the tree. Trees without guards will only last a few days before the rabbits and deer snip off them growing tip. Guards without the correct number of zip-ties are likely to blow over in the wind and snap the tree they are guarding. Trees with bent over stems will likely die because it will mess with the gravity flow of auxin down the stem. If the stem is threaded through a zip-tie the zip-tie will choke off the main growing tip as the stem thickens.

I think the next project for the farm is to plant some more fruit trees and expand the orchard. There is an old goose garth which is adjacent to the existing orchard, but has been used for sheep grazing for many years. I’d like to plant apple trees, plum trees, and maybe some cherry trees. We have a couple of cherry trees on the farm, but they only produce a crop every few years. I imagine this planting will be very different to the woodland planting. The fruit trees will likely be larger when we buy them, and will require more substantial guards as losing 1 of a total of 10 fruit trees is more detrimental than losing 10 out of a total of 100 woodland trees.

In the next few years our main concern in the new woodland is going to be keeping the grass mown around the trees, which without the sheep to graze it will grow very fast. If we don’t keep on top of the grass it could overshadow the trees and affect their growth. It could also cause the land to become shrubby thicket, which we don’t want.

The project was expensive, but most of this cost came from the tree planting company, and the MOREWoods scheme helped enormously to keep the cost of the trees down:

| Item | Cost (£) |

|---|---|

| Fencing | 2508.00 |

| Trees | 1584.00 |

| Planting | 5858.40 |

Observing how a professional tree-planting company organises planting a woodland has given me a lot of confidence that if I choose to do something like this again, I could easily make up for the lack of expertise by having more volunteers and managing them properly. I would have to spend a lot of time teaching to make sure everybody knew how to plant a tree and make sure that the planting area was marked out properly, but it would be worth it. It seems like giving each person a small job, like laying out stakes in the right place, or distributing trees to other volunteers is the best way to make the job more efficient.