Recently I spent a month in Namibia on fieldwork. I was working in a place called Ongava Game Reserve on the south side of Etosha National Park. Ongava is a privately owned game reserve with a research centre attached, the Ongava Research Centre (ORC). I was working with a team of students from NUST, the Namibia University of Science and Technology, and our aim for the field campaign was to set up some vegetation monitoring plots within the Reserve.

The plots we established are very similar to the plots I set up in Bicuar National Park in Angola during my PhD. The plots are 100x100 m squares. Within each plot we measure every woody stem with a diameter >5 cm at breast height (DBH, 1.3 m). For each stem we record the diameter, species, the tree to which the stem belongs, the location of the stem within the plot using tape measures, information on mortality, and damage, following the SEOSAW tree plot protocol . Each of these stems is then tagged by nailing a numbered aluminium into the stem. We deliberately nail the tags 20 cm above the diameter measurement, so in a few years time we can return and measure the same trees at the same place on the stem to see how much they have grown.

We used a vegetation map developed by Vera De Cauwer at NUST to determine the major vegetation types on the Reserve and to pick potential locations for the plots ahead of time. The majority of the land area of the Reserve is covered by woodland dominated by Colophospermum mopane and to a lesser extent Terminalia prunioides. Most of this woodland occurs on rocky rolling hills composed of Elandhoek light-grey dolomite with thin dark clay soil. There are also Mopane-Terminalia woodlands on some different rocky hills composed of Huettenberg formation darker-grey dolostone, which has bands of chert running through it. These woodlands tend to be more diverse and include species not found elsewhere like Kirkia acuminata, Sterculia africana, and Moringa ovalifolia. Around the base of the hills this woodland grades into bushland, also with Colophospermum mopane and some Terminalia prunioides, but shorter stature (height <4 m) and with fewer proper trees (single trunk with branching canopy on top). On the deeper clay-silt soil on the flat land, underlaid by calcrete, there is a mixture of sparse mopane parkland that is heavily grazed by ungulate herbivores, sparse to dense shrubland dominated by Catophractes alexandri, and grassland with very sparse Acacia species.

Our aim was to establish 8-10 plots covering the dominant vegetation units in the Reserve. This includes some areas with few or no trees like the Catophractes shrubland and open grasslands. We established two plots in the open mopane parkland areas. Two plots in Catophractes shrubland. Two plots in grassland. and 6 plots in the Mopane-Terminalia woodland. In the woodland we aimed to try and capture some of the variation in species composition and stand structure, with some plots in less diverse areas and some on the more diverse Huettenberg hills. So in total we established 12 plots, though the grassland and Catophractes plots were very easy to set up. The real work on those plots will come later when others use the ground layer and shrub/small stem SEOSAW protocols to assess the non-tree vegetation.

The parkland is quite interesting. On one of our plots, even though there were only 117 trees, there were 342 stems. Most trees had two or more stems. One tree had 13 stems. It’s probable that on some of these parkland areas, the land was previously cleared, or at least the big trees were felled, when the Reserve used to be a farm.

Finding decent plot locations in the Mopane-Terminalia woodland areas on the rocky hills was more challending than I expected. There are not many roads going through these areas of the Reserve, making large tracts of land essentially unreachable if we are carrying all our equipment. On top of that, one of the main routes to access the southern reaches of the Reserve was cut off for about two weeks due to heavy rain that made it too muddy to get a vehicle through.

We also had trouble marking the plot corners in the rocky areas. Normally we hammer rebar into the ground to mark the plot corners. But on the rocky hills this was almost impossible. Even if we found a gap in the rocks at one corner, it almost certainly wouldn’t coincide with gaps at the other three corners. We resorted to maneouvering huge boulders into place for most of these plots and painting them, then triangulating the corner location by measuring from many nearby trees.

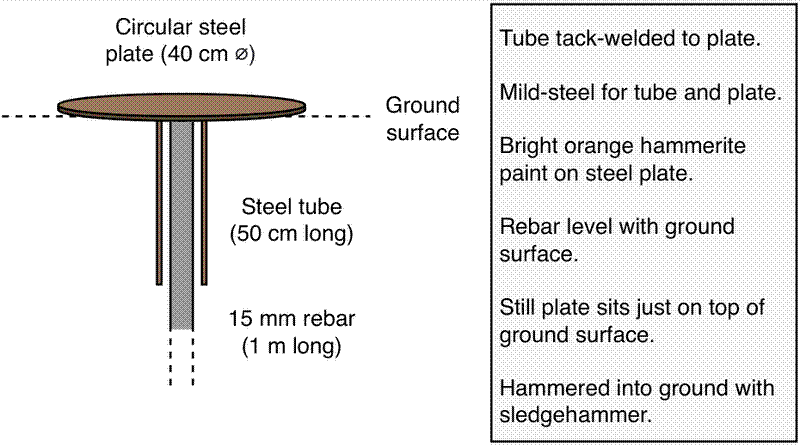

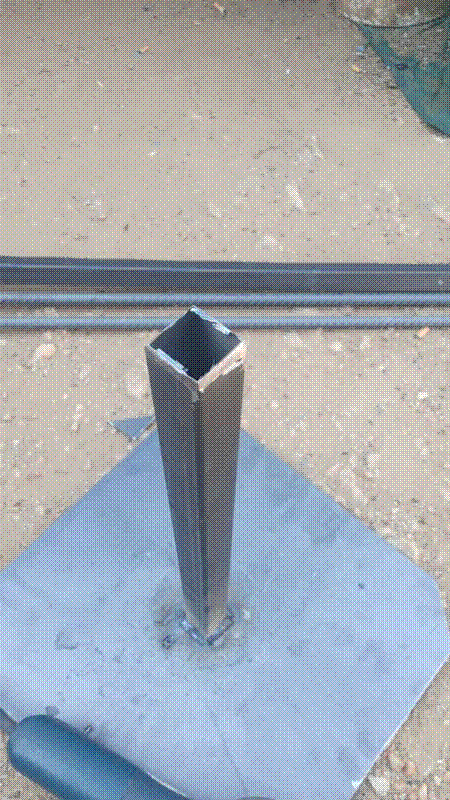

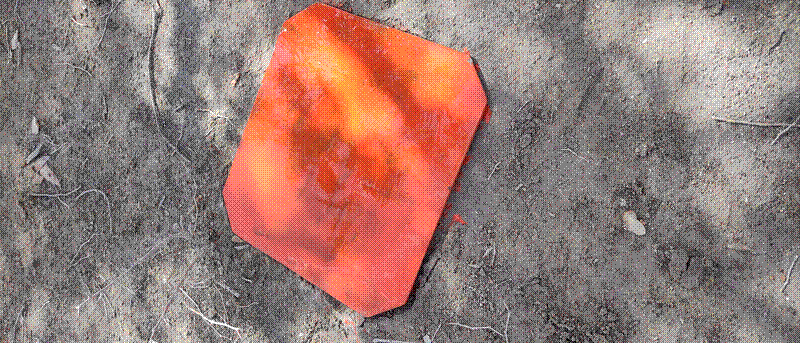

In Ongava, the management are concerned about animals injuring themselves on bits of metal rebar sticking out of the ground. For those areas on the deeper clay soil where we could get a marker in the ground, I designed an alternative to rebar that remains secure and poses no danger to animals. The marker is made from steel plate, welded to a length of square steel tube. The tube is then hammered into the ground and the plate sits flush with the surface. The plate can then be painted to increase visibility.

In 2024 I hope that the we can do the shrub and ground-layer protocols, then in 2025 it will be time for the first recensus of the large trees. After that, we should fall into a routine of surveying these plots every 3-5 years to track the growth and mortality of the trees, and trends of vegetation change.