This paper was recently published :

Mo, L., Crowther, T.W., Maynard, D.S. et al. The global distribution and drivers of wood density and their impact on forest carbon stocks. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 2195–2212 (2024).

In the paper, the authors use plot data from 1.1 million forest plots, and wood density data from 10,703 tree species, to explore global patterns in wood density. They find that water availability, measured in their case by mean annual temperature and soil moisture, is correlated with wood density, globally. They suggest that the mechanism for this is that trees in “warm and dry regions are likely to develop denser wood to maintain xylem resistance against implosion and rupture”.

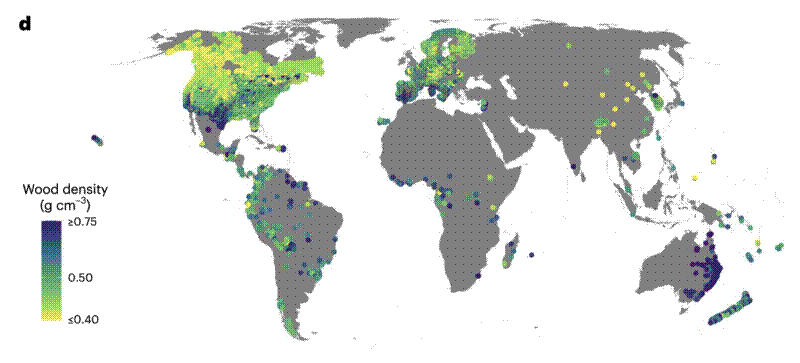

Notably, this study included hardly any plot data from the seasonally dry tropics, including tropical savannas and dry forests. There is a particular lack of data from southern Africa:

The authors use random-forest models to develop wall-to-wall maps of predicted wood density across forested landscapes.

In my post-doc, we have amassed a dataset of ~1500 plots from across the seasonally dry tropics, for which we have estimates of wood density for each tree (>5 or >10 cm diameter). We used wood density data from the Global Wood Density Database (Zanne et al. 2009) with extra data from Vieilledent et al. (2018). We used the BIOMASS:getWoodDensity() function to estimate individual tree wood density, which uses the species estimate where possible, then genus, family, and finally plot-level if no data is available.

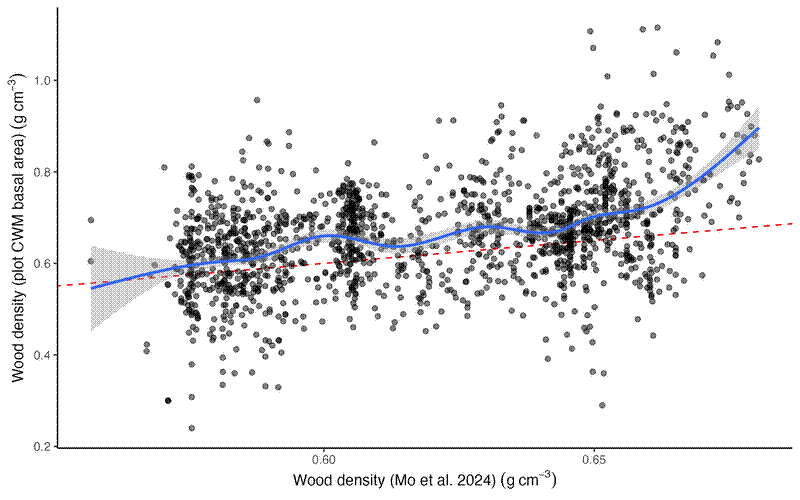

As in Mo et al. (2024), I took the Community Weighted Mean (CWM) of wood density by basal area from each plot, using the most recent census for each plot.

Below is a plot comparing our estimates of the CWM of wood density from each of our plots, with the corresponding pixels from the community wood density map in Mo et al. (2024) (see Figure 3a in the paper). The line is a GAM smooth fit:

I think this shows good agreement between our plot-level estimates and the spatialised estimates from the paper. We show greater variation in wood density, but the average wood density of our plots at any level of Mo et al.’s estimates is about the same.

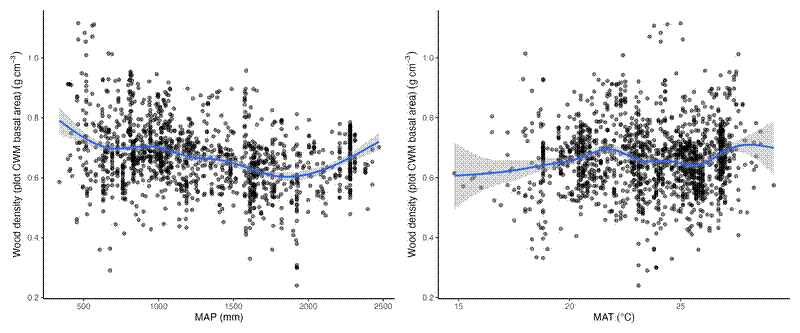

We do not however, see strong relationships between plot-level wood density estimates in the seasonally dry tropics with precipitation or temperature (ERA5-Land 1980-2022). There is a weak negative correlation between precipitation and wood density, as in the paper, but we don’t see any effect of temperature, which the paper regards as the strongest environmental filter acting on wood density.

This might because our data, which span the environmental space of woody ecosystems in the dry tropics, don’t cover a wide enough environmental gradient to detect an effect of temperature, while the data in Mo et al. (2024) cover a wide range of biomes across a broad latitudinal range.

From this basic comparison, it seems like the lack of data from the seasonally dry tropics hasn’t harmed the estimates in Mo et al. (2024). I wonder though, if they did add more data from the seasonally dry tropics, would they find a stronger effect of fire disturbance, and a weaker effect of temperature on wood density? The authors acknowledge that their dataset of global “forests” might under-represent fire, and there is a clear bias towards temperate and boreal regions in their plot data.

I see this wood density map being especially helpful in building biomass maps from radar or LiDAR data, which can sense woody volume, but not wood density. For plot-level analyses however, using an individual-level estimation of wood density will remain the better option.